Besonders ist, dass Ann Petry wirklich die erste schwarze Frau war, die in den Vereinigten Staaten veröffentlicht wurde, bis dahin waren es nur weiße. […] [The Street – Die Straße] zeigt die Grenzen zwischen schwarz und weiß, die unüberwindbar sind, auch zu Hass führen, und die Vorurteile, die daraus entstehen.

Die Kritikerin Birgit Koß im Deutschlandfunk Kultur Podcast über die deutsche Übersetzung aus dem Amerikanischen Englisch, welche im Februar 2020 bei Nagel & Kimche in Zürich erschienen ist. Ihr Fazit im Text online: In wortgewaltigen Bildern lässt Ann Petry das Leben in der 116ten Straße während des Zweiten Weltkrieges erstehen, ausgezeichnet übersetzt von Uda Strätling. Ein zutiefst berührender und analytischer Roman, der als erster seiner Zeit die Situation der schwarzen Frau in den Blick genommen und leider viel zu wenig an Aktualität verloren hat.

2022 erschienen von Ann Petry bei Nagel & Kimche: The Narrows, übersetzt ins Deutsche von Pieke Biermann, und Harriet Tubmann, übersetzt von Hella Reese.

https://www.deutschlandfunkkultur.de/ann-petry-the-street-die-strasse…

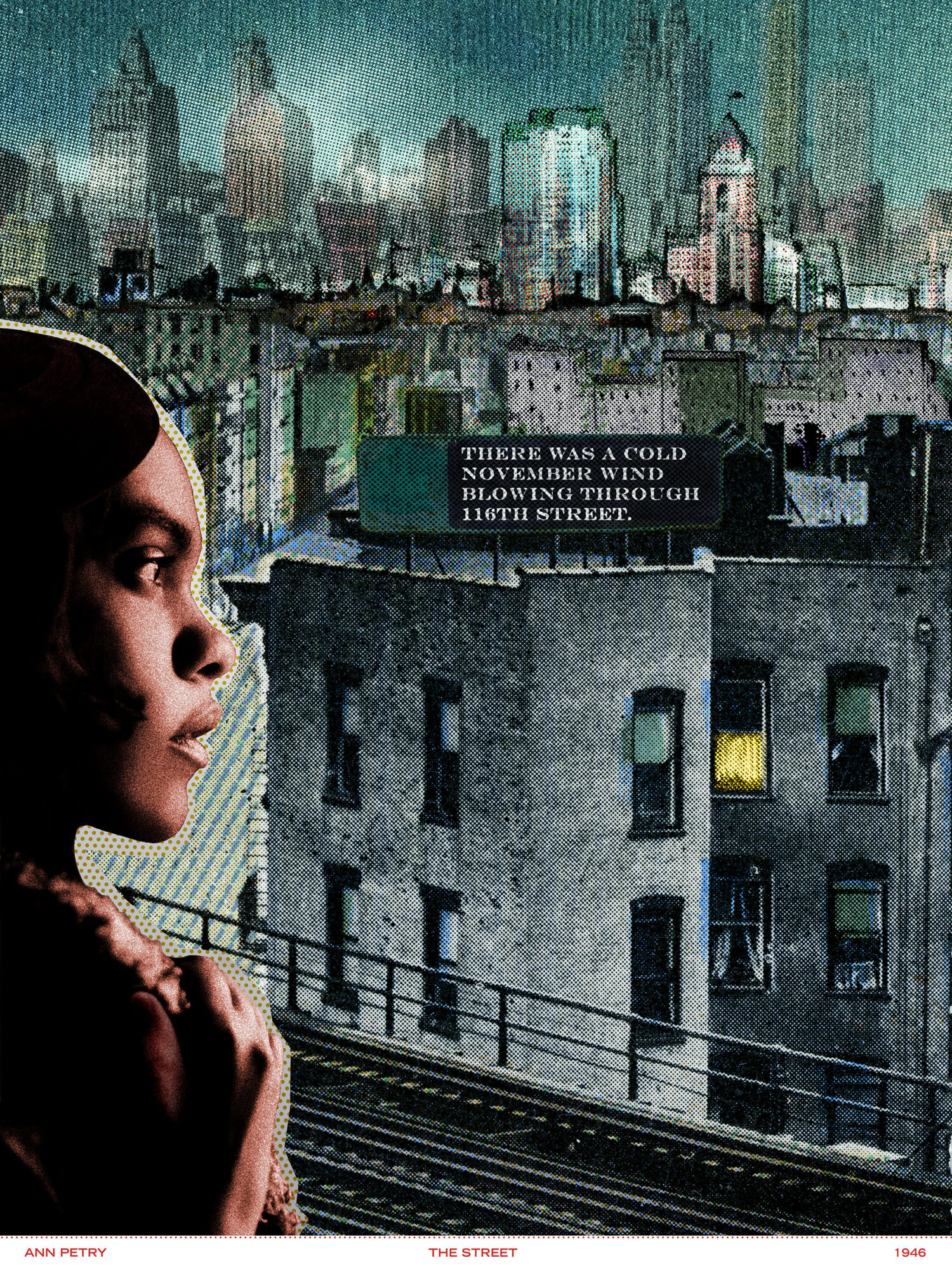

It is special that Ann Petry was the first black woman ever to be published in the United States, until then it had only been white women. […] [The Street] shows the boundaries between black and white, which are insurmountable and may lead to hatred, also the prejudices that arise from it.

The critique Birgit Koß about the German translation in Deutschlandfunk Kultur podcast, published in Febraur 2020 by Nagel & Kimche, Zurich. Her conclusion online: In eloquent images, Ann Petry brings life on 116th Street during World War II to life, excellently translated by Uda Strätling. A deeply moving and analytical novel that was the first of its time to focus on the situation of black women and, sadly, has lost far too little of its relevance.

First paragraphs of the novel:

There was a cold November wind blowing through 116th Street. It rattled the tops of garbage cans, sucked window shades out through the top of opened windows and set them flapping back against the windows; and it drove most of the people off the street in the block between Seventh and Eighth Avenues except for a few hurried pedestrians who bent double in an effort to offer the least possible exposed surface to its violent assault.

It found every scrap of paper along the street – theater throwaways, announcements of dances and lodge meetings, the heavy waxed paper that loaves of bread had been wrapped in, the thinner waxed paper that had enclosed sandwiches, old envelopes, newspapers. Fingering its way along the curb, the wind set the bits of paper to dancing high in the air, so that a barrage of paper swirled into the faces of the people on the street. It even took time to rush into doorways and areaways and find chicken bones and pork-chop bones and pushed them along the curb.

It did everything it could to discourage the people walking along the street. It found all the dirt and dust and grime on the sidewalk and lifted it up so that the dirt got into their noses, making it difficult to breathe; the dust got into their eyes and blinded them; and the grit stung their skins. It wrapped newspaper around their feet entangling them until the people cursed deep in their throats, stamped their feet, kicked at the paper. The wind blew it back again and again until they were forced to stoop and dislodge the paper with their hands. And then the wind grabbed their hats, pried their scarves from around their necks, stuck its fingers inside their coat collars, blew their coats away from their bodies.

The wind lifted Lutie Johnson’s hair away from the back of her neck so that she felt suddenly naked and bald, for her hair had been resting softly and warmly against her skin. She shivered as the cold fingers of the wind touched the back of her neck, explored the sides of her head. It even blew her eyelashes away from her eyes so that her eyeballs were bathed in a rush of coldness and she had to blink in order to read the words on the sign swaying back and forth over her head.

[…]